In early October of 1347, 12 trading vessels arrived at the Port of Messina in Italy after an excursion to the Black Sea. The ships quickly caused a stir as they uncharacteristically struggled to dock—it would soon become clear why that was. Onlookers watched as crew members emerged from the ships—they were described as looking like skeletons covered in black boils, and the larger boils were ruptured, bleeding, and oozing with pus.

There were very few of these "skeleton men" because most of the crew members on these ships had died during during the journey. This mysterious disease would take the lives of not just the few surviving crew members, not just the people who interacted with them, but everyone who was even in the vicinity of the ships. A contemporary account from Michael Platiensis, and translated by C. H. Clarke describes the onset of the disease:

This infected the whole body and penetrated it so that the patient violently vomited blood. This vomiting of blood continued without intermission for three days, there being no means of healing it, and then the patient expired.

-Michael Platiensis

Any attempt to contain this disease—which had already been decimating parts of Asia and Northern Africa—had failed. People trying to escape this imminent death would just bring it with them. Over the course of seven years, the Bubonic plague had killed an estimated 50 million people—almost half the population of Europe. Throughout history, there had been a lot of theories about what might have caused this disaster—perhaps it was a punishment from God?

There's also something called Miasma theory, which asserts that pandemics—and apparently also obesity—are caused by various forms of bad air.

In the case of the plague, it was thought that this bad air was caused by a Mars-Saturn conjunction, during which the planets Mars and Saturn look like they're close together when viewed from Earth. It should be noted—and I feel like some percent of you, after I say this, are going to become Miasma theory believers—but it should be noted that this planetary alignment would happen once again in 1373, during which the plague was having a bit of a resurgence.

But, it should be noted that there are also two other resurgences before that without the Mars-Saturn conjunction.

The true source of this disease would actually not be fully determined until 1894, during an outbreak of the plague in Hong Kong. Sent on a mission from the French government, a young bacteriologist named Alexandre Yersin was sent to investigate. When examining the patients, he would discover a bacterium that would come to bear his name, Yersinia pestis. But how does this bacteria get there? Due to reports of dead rats being found before plague outbreaks, Yersin theorized that rats were somehow connected, and testing dead rats would in fact reveal that they did carry this bacteria.

But clearly, rats weren't just going around biting people and then they die. The cause would be really obvious then. The actual connection would soon be discovered by Paul-Louis Simond, another French biologist investigating the outbreak. After learning that people who handled the dead rats had also become infected, he suspected that the infection might actually be caused by the fleas that the rats carry—and testing the fleas would, in fact, reveal that they were the ones carrying it. He also found that the bacteria starves the fleas, which makes them feed much more aggressively.

And then when their preferred meal, the rats, are all dead, it's only then that they basically move on to anything else—including people.

And now, at this point, you're probably wondering, "When the fuck did this become the history channel?" This is just the third episode of this series, and we already got to go back to the 14th century? Well, you see, this ain't just history. A lot of you probably think of the Bubonic plague as this thing that it came in the Middle Ages and wiped out half the population, and that was the end of it. That isn't so. Globally, there's still about 1,000 cases of the plague a year.

When I say globally, you're probably like, "Oh yeah, sure, those 'other' parts of the world. Oh, Madagascar, that's not a real place."

Well, let me tell you about a man in New Mexico. On March 8th of 2024, the New Mexico Department of Health issued a statement revealing that an anonymous man had died of the plague. Although the plague is now curable with antibiotics, this man would succumb to the disease, making him the first plague death in the US since 2021, which also is probably more recent than you thought.

The statement went on to outline safety precautions to prevent getting the plague. In particular, you want to avoid contact with wild rodents like rats, rabbits, and squirrels, particularly in New Mexico.

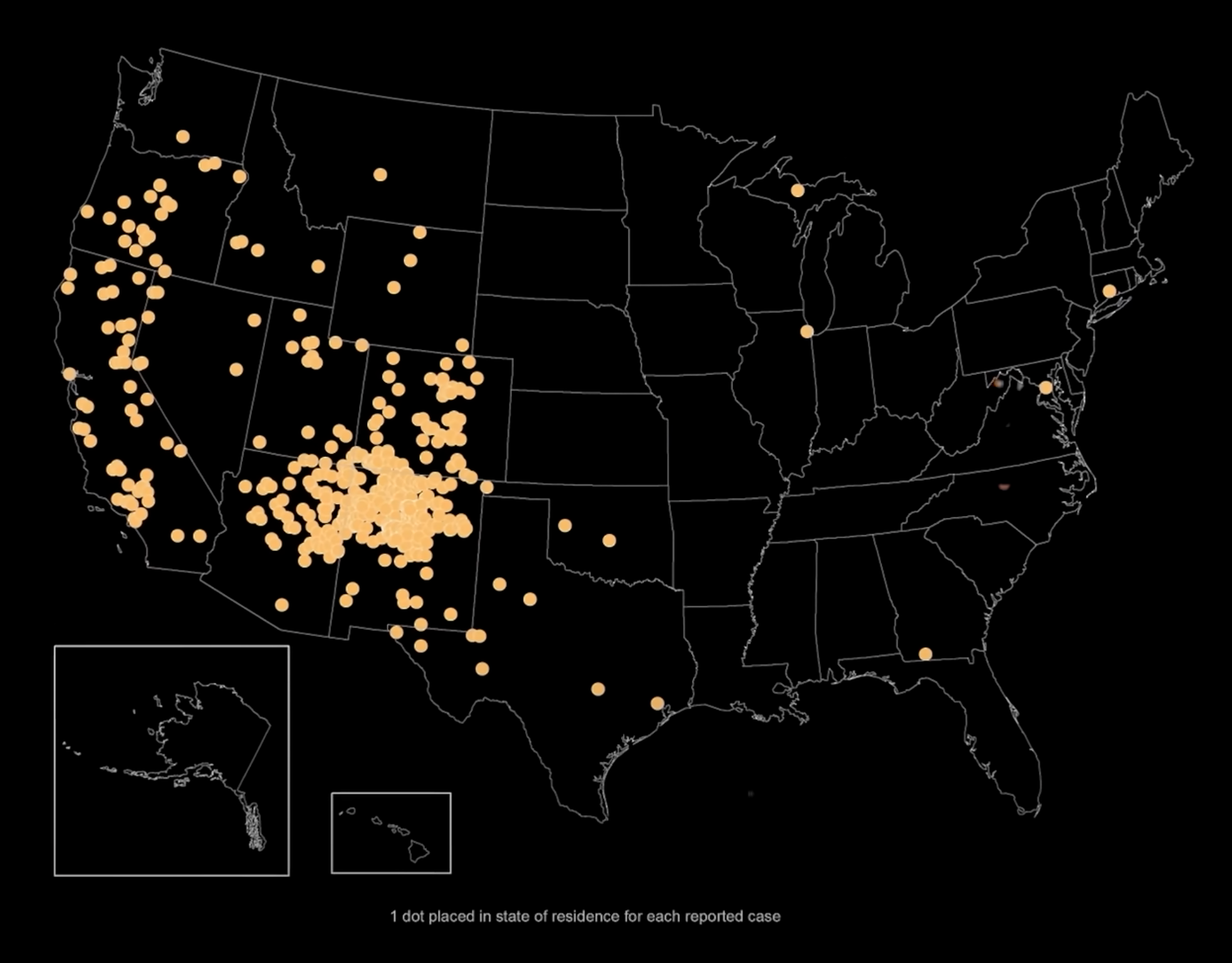

In New Mexico, and the Western US in general, these animals are known to carry plague fleas. These safety precautions include making sure your pets don't come into contact with these animals. They pointed to another recent case in Oregon. This woman who lived in Oregon had gotten the plague from her cat. Fortunately, she survived—but her cat did not. On average, the US has seven cases of the plague a year with just 15 deaths reported between 2000 and 2023. It's highly curable now, especially when caught early. Due to generally better hygiene in the world and the fact that when you get the plague, it's extremely visible, it's unlikely that this disease will ever be the one to wipe us all out again. But as is the case with a lot of bacterial infections, there are concerns that growing antibiotic resistance could make the disease more deadly in the years to come.

For today's video, let's take a look at the "Wacky World of Getting Killed by Rodents."

Hamsters are famous for dying in insane, horrific ways. You'll find countless threads around the internet with thousands of unique ways that hamsters have died, crushed, exploded, electrocuted, you name it. Oftentimes, it's because they're given as pets to children who aren't prepared to take care of a living thing—but also, hamsters are just fragile creatures.

But what if a hamster got its revenge on the human race? It's more likely than you think.

In October of 2024, an anonymous 38-year-old Colombian woman collapsed mere feet away from the door of the Carinyana Health Center in Spain. Nearby staffers spotted her and attempted to revive her, but to no avail. The woman—accompanied by her two children, aged 11 and 17—had died. When the children were questioned, they said that their mother complained that she hadn't been feeling well for the for the last several hours, and this has gotten to a point where she knew she had to get medical help. This general feeling of malaise began after she was bitten by the children's pet hamster. Although it was never publicly confirmed whether or not this was the true cause of her death, it was noted that she suffered from severe asthma, which would greatly increase the chance of a severe allergic reaction being fatal. It was also noted that, although allergies to hamster bites are very rare, if a bite is deep enough, it can cause a very severe reaction.

Similarly, in May of 2018, it was reported that a retired Singaporean policewoman died after being bitten by her pet hamster. The woman was reported to have been a big fan of hamsters—she posted about them all the time, and she had two of her own. Then one day, the two hamsters get in a fight. She goes to break up the fight, and as she's pulling them apart, one of them bites her. In the time following the bite, her tongue became numb, and she began to lose feeling in one of her hands. Then as the symptoms progressed, she fell into a coma, and after six days in a coma, she passed away.

The reporting around this particular story had gotten to a point where people were debating whether or not it was actually safe to have a hamster as a pet at all. But Singaporean hamster enthusiasts were quick to point out that literally anything in the world could cause a severe allergic reaction. And a doctor commenting on the case noted that it's very rare to die from a hamster bite because they don't produce venom. Interestingly enough, as a side note, I'm noticing that most of the hamster bite deaths I'm finding seem to be in Asia. That makes me wonder if perhaps Asians are more likely to have hamster bite allergies, or perhaps the hamsters in Asia carry more, or different, allergens. It could also be that Asian news outlets are just more interested in talking about this sort of thing. But in any case, as far as I can tell, it's not something that's been specifically investigated.

Here's the case of another police officer, this time in Japan. In June of 2002, the police officer was sent to investigate reports of a ferret loose in a park in Ōita Prefecture. After finding the criminal rodent, he tried to arrest it, but was bitten on his hand. It's unclear whether or not he successfully captured the beast, or for that matter, whether the ferret was feral or if it was an escaped house pet. But in any case, the consequences would eventually be fatal—although not as quickly as with the hamster. After he was bitten by the ferret, it was likely that the area around the wound swelled up a bit and hurt—but, y'know, he got bitten, that might seem kinda normal. But, in fact, that was the beginning of a deadly bacterial infection. Three months passed and the symptoms began to get much worse. And after having it checked out, it turned out that he had cellulitis.

Cellulitis is a skin infection that's generally caused by the staff or strep bacteria. Antibiotics will typically clear this up, but have left untreated, or if the infection is particularly severe, it'll eventually spread into your lymph nodes and throughout your bloodstream.

Consequentially, the police officer would spend the next 17 years battling health problems because of this ferret bite, ultimately passing away in January of 2019.

There was some pushback to attributing his death to the ferret bite because since it happened on duty, his family would be entitled to compensation from the government. But ultimately, in November of that year, the investigation concluded that his death was caused by that ferret bite 17 years prior.

The theme for this episode actually came about when I was talking about rat piss with my friend Susu. Here she is to tell you about yet another rodent-born illness.

Susu:

What do the deaths of a 26-year-old hotel employee, actor Gene Hackman and his wife, classical pianist, Betsy Arakawa, as well as multiple strange deaths in the California and New Mexico region all have in common? All were murdered by the same psychotic killer, the deceptively cute and harmless... North American mouse!

These adorable but evil peddlers of pestilence are some of the only known carriers of the rare and deadly hantavirus. It begins with flu-like symptoms and spirals out of control, leading to often fatal lung and heart problems. The first known case originated in 1978 in South Korea, near the Hantan River, of which the disease gets its name. This, too, was the dastardly doing of none other than the devious apodemus agrarius, commonly known as the striped field mouse.

The mice are to blame!

This extremely rare virus is what caused 26-year-old Rodrigo Becerra's life to be cut tragically short this March after he was exposed to the deadly contagion via rat droppings discovered at his place of work, the Mammoth Mountain Inn, located in Mammoth Lakes, California.

I'd hate to look at those Yelp reviews. Three other deaths reported to have occurred in the same location. Coincidence? I think not. Antivirus was the culprit once more.

This is the very virus responsible for the passing of 65-year-old Betsy Arakawa in her New Mexico home on February 11th. Her husband, Gene Hackman, did not report her death. Why? Because he was dead!

New Mexico chief medical examiner, Heather Jorelle, explained this was likely due to Hackman, 95, suffering from late-stage Alzheimer's disease—oh.

The last recorded activity on the late actor's pacemaker was reported on the 17th, but his body tested negative for hantavirus. Hackman likely passed a week after his wife from cardiovascular disease and Alzheimer's. So, okay, maybe the mice didn't kill him, but they were clearly a part of it—they conspired.

So let these tragic stories serve as a cautionary tale: Hantavirus has no cure, no vaccine, only treatment, and a 30 to 50% mortality rate. Don't disregard the horrors of Hanta-hell just because there's only ever been a few hundred cases reported in the United States since 1993. The mice want us to downplay their atrocities. They are lying in wait to strike us when we least expect it. A rodent ruprising is at hand.

Protect your home from the mice menace. Call your friendly neighborhood exterminator to report any suspicious rodentivities. And live long enough to see the Apocalypse.

I'm Susu, reminding you to be secure, contain the virus, and stay protected. Thanks, Justin, for letting me be in your radio.

Back to Whang:

In April of 2005, a woman from Rhode Island began to suffer from an intense headache. This headache would persist for a week and ultimately culminate in a stroke that paralyzed one side of her body. Over the next few days, her symptoms would worsen, and in a few days, she was completely brain dead. Throughout her life, the woman had a history of hypertension, and it's likely that that is what caused this to happen to her eventually. Upon her death, her family opted to donate her organs, feeling that it's what she would have wanted—to give someone else the gift of life. Six recipients were soon found. People received her liver, her lungs, two kidneys, and two corneas.

Then the unexpected happens.

Within just three weeks, four of the recipients began to show signs of an infection: fever, diarrhea, rashes. As the symptoms progressed, three of these four recipients died in under a month, each one of them suffering from liver failure. It was clear that something was wrong with these organs, but how could that be? The woman didn't die from any an infection, she had a stroke related to hypertension. Everything that happened to her was consistent with her known medical history, and there's no reason why those organs should have been unsafe.

They were sure that it had to be some kind of an infection, but they were baffled as to how or what or why. After testing some tissue samples from the patients and the woman, it was found that all the organs contained a virus called LCMV, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, typically found in the pee and pooh of mice and rats.

Now, while this sounds very gross, it's very likely that some of you have had this in your system. Maybe you have it right now in your system, but you don't know because usually you don't get any symptoms at all from it. At most, maybe a little case of the sniffles. However, when you receive an organ transplant to help your body accept the organ, they put you on drugs that suppress your immune system. Now, all of a sudden, you have this virus that normally does nothing, and it's free to wreak havoc on your body. Fortunately for the fourth organ recipient, they figured this all out before it was too late. They reduced the amount of immunosuppressants he was on, and he survived. Now, back to the donor, she had no signs of this virus at all—died of causes that certainly had nothing to do with it.

So they were trying to figure out how it got into her system. At first, they were investigating for rat infestations, mice infestations, but they couldn't really find anything. And then they found out that one of her family members had just gotten a pet hamster. This family member was also the only one who also tested for antibodies to the virus. While they couldn't 100% rule out the possibility that she did get it from a mouse or a rat, in all likelihood, she did get this virus from the hamster.

The Rhode Island Health Department assured the public that what happened here is exceptionally rare, and people receiving organ donations shouldn't be afraid of this happening. In fact, the CDC only had a record of this ever happening one time before out of millions of organ donations.

But you just got to understand, a hamster doesn't need to bite you to kill you.

--Shout out to Susu for helping with this story. Visit her YouTube channel here.